When we think of an author, the stereotypical image that comes to mind is that of a recluse, cut off from the rest of the world, trying to invoke the Muses into endowing zir with inspiration. What we do not realize is that this image is inherently flawed as it assumes that creative inspiration comes from a vacuum and a writer can find language by marinating in zir own thoughts. The creative process, however, is in fact a social process and “our creativity has its roots in the work of others – in response, reuse and rewriting.” (Harris, 2006) Creativity is the process of integration of previous creative work in relation to the social world.

The word “text” has its origins in the Late Latin past participle stem of texere meaning “to weave, to join, fit together, braid, interweave, construct, fabricate, build,” from the Proto-Indo-European root teks which means “to weave.” Julia Kristeva no doubt had this in mind when she described every text as “a mosaic of quotations.” In her view, all text was a tapestry, the fabric for which was provided by other texts and the social world. “Any text is the absorption and transformation of the other” for Kristeva. With this statement, Kristeva introduced a new way of looking at the creative process. Kristeva defined the creative process, not as the process of creating an original work but the process of creating a unique conglomeration of existing work (literary text) and the social world (the social text). Essentially, all texts derive their meaning from other texts and that texts are not created ex nihilo.

The idea of an author as an original creator comes from the Romantic belief in creative genius. St. Bonaventure’s 13th century distinction is very relevant here:

A man might write the works of others, adding and changing nothing, in which case he is simply called a “scribe” (scriptor). Another writes the work of others with additions which are not his own; and he is called a “compiler” (compilator). Another writes both others’ work and his own, but with others’ work in principal place, adding his own for purposes of explanation; and he is called a “commentator” (commentator) . . . Another writes both his own work and others’ but with his own work in principal place adding others’ for purposes of confirmation; and such a man should be called an “author” (auctor). (Eisenstein, 1979)

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is an amazing example of the “author” as St. Bonaventure describes it. Just as the subject of Frankenstein is made by stitching together different body parts into a single monstrous body, the book itself is written by weaving different texts into a “simple monster story.” Shelley incorporates multiple intertextual sources into her work and the book takes a different interpretation based on which text the reader chooses to focus on. By leaving her own perspective ambiguous, Shelley gives over the power of interpretation to the reader. If read from the lens of Paradise Lost, Frankenstein is a creation myth; if read from the perspective of Wollstonecraft, it’s a cautionary tale against bad parenting but if read from the perspective of Darwin and Paracelsus, Frankenstein represents “the first seminal work to which the label SF [Science Fiction] can be logically attached.”(Aldiss, 1973) But the intertextual beauty of Frankenstein only begins with Shelley’s work. Frankenstein has integrated into the social fabric over its almost 200 year existence. From Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl to the appearance of Franken-Girl in Disney Channel Original Series Wizards of Waverly Place, references to Frankenstein are inescapable in modern Western Society. Just as Shelley forwards her own extensive reading in Frankenstein and allows for interpretation in her work, those who seek to forward her work to produce new texts show the same spirit of intertextuality. Jackson’s Patchwork Girl weaves Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and L. Frank Baum’s Patchwork Girl of Oz among other texts to create a truly unique (dare I say, original?) tapestry of text.

This is consistent with Barthes’ view that “a text consists of multiple writings, issuing from several cultures and entering into dialogue with each other, into parody, into contestation; but there is one place where this multiplicity is collected, united, and this place is not the author, … but the reader.” Barthes would argue that by refusing to assign an “ultimate meaning” to the text of Frankenstein, Shelley has liberated the reader from the authoritative grasp of the author and that Jackson is doing the same thing with the hypertextual structure of Patchwork Girl. Barthes makes the argument that the concept of the “Author-God” is a modern one and a result of capitalist ideology and seeks to replace it with the concept of the “sciptor” who might inscribe text but does not ascribe any meaning to it. This interpretive perspective of literature leaves the reader free to form any associations and trace the threads in the tapestry between different texts, intended or otherwise, as the will of the author cannot ascribe meaning. The larger implication of this is that “every text is eternally written here and now” (Barthes) by the reader. The text is no longer a product ready to be read but an ever-expanding, evolving and never-ending process. Barthes would argue that the shift from product to process marks the “birth of the reader” as “ransomed by the death of the author.” Once the text is free from the hegemony of the author, the reader is finally liberated and has full control of assigning meaning to the text.

However, this goes against the very premises of intertextuality as defined by Kristeva. The notion of intertextuality requires the complex system of language to come together in order to assign meaning to a text as it is based on the Sausserian principle of free play of signifiers. Once one accepts the notion of intertextuality as defined by Kristeva, it follows that the reader has no more power to ascribe meaning than the author does. The reader is merely a vacuum in which multiple texts come together to form a tapestry of meaning. Perhaps, intertextuality does not lead to the death of the author and the birth of the reader as Barthes puts it but into the blurring of the line between reader and writer. Reading becomes the locus of writing and every individual who views the tapestry of a text and forms associations adds to it in forming those associations. The writer and the reader merge into one as they collaborate to assign meaning to a text. Another helpful way to resolve this contradiction would be to use E. D. Hirsch Jr.’s distinction between “meaning” and “significance.” Hirsch’s concept of authorial intention basically draws a distinction between the meaning that the author assigns to the text, it’s “meaning” and how that relates back to the reader, its “significance.” Hirsch thinks that the author does assign meaning to the text but the reader is free to interpret the text in zir own way and assign a different meaning to it as long as ze do not misrepresent zir interpretation as the author’s intention. Hirsch’s perspective of literature does assign an “ultimate meaning” to the text but allows some space for reader interpretation.

The notion of intertextuality influences several aspects of the literary experience. It affects the connection between the author and the text; it disrupts the relationship between the author and the reader and it influences how the reader interacts with the text. But the precise nature of this influence and the full extent of its implications is still being explored.

Works Cited

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 2006. Print.

“Online Etymology Dictionary.” Online Etymology Dictionary. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Dec. 2016.

Kristeva, Julia, and Toril Moi. The Kristeva Reader. New York: Columbia UP, 1986. Print

Eisenstein, Elizabeth L. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Communications and Cultural Transformations in Early Modern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1979. Print.

Aldiss, Brian W. Billion Year Spree; the True History of Science Fiction. Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1973. Print.

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Richard Howard. (n.d.): n. pag. Web. 2 Dec. 2016. <http://writing.upenn.edu/~taransky/Barthes.pdf>.

Hirsch, E. D. “Meaning and Significance Reinterpreted.” Critical Inquiry, vol. 11, no. 2, 1984, pp. 202–225. www.jstor.org/stable/1343392.

Jackson, Shelley. Patchwork Girl, Or, A Modern Monster: A Graveyard, a Journal, a Quilt, a Story & Broken Accents. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems, 1995. PowerPC.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, David Lorne Macdonald, and Kathleen Dorothy Scherf. Frankenstein, Or, The Modern Prometheus. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 1999. Print.

ORIGINALS

NARRATIVE, DISCOURSE AND LITERACY

Literacy is technically defined as the ability to read and write. However, literacy is a much wider, more complex concept that has existed before the invention of paper. Literacy has to do with communication; effective communication. Literacy is the ability to clearly comprehend what someone else is trying to express and properly articulate one’s own thoughts.

The Origin of Literacy

Wendell Berry feels that in order to know a language that expresses the truth about the world as we see it, “we must know something of the roots and resources of our language.”(1972) The origin of every single language is in its oral tradition and the very first stories of every culture began in the oral tradition. This is also the origin of literacy.

Social transmission was an important goal for elders in traditional societies. It was essential to communicate moral values and cultural norms to the younger generation. However, there were challenges to that. One of the major challenges was that of interest and another was of cultural taboos. Storytelling and myth were effective tools of communicating information that was not necessarily interesting or the discussion of which was tabooed. The inherent symbolism and metonymy of mythological stories made it possible to apply the human condition to the divine in order to make conversations about them possible.

The Institutionalization of Literacy

The institutionalization of literacy and the constant focus of governments on their countries’ literacy rates has led to a trade of quality for quantity. The very definition of literacy has been boiled down to the ability to read and write a simple sentence in any one language. Where once, to be called truly literate, one had to have an intimate knowledge of various languages, classic texts and high culture, and be able to discuss any topic in great depth and with unique insight. Today, the label of “literate” can be given to anyone who is able to read and write regardless of whether that individual can comprehend what ze reads or properly express what ze is trying to say or understand the full implications of what ze does say.

When Berry moans about the “published illiteracies of the certified educated” (1972), he is not distressed about the ability of an individual to convert symbols on a page to sounds and sounds to symbols but about the inability of most individuals to peel back the surface layer and comprehend the significance of the words themselves. He is distressed about the “lack of a critical consciousness of language”(1972). His concern is not with the fact that a large number of people cannot read but with the fact that many who can read and call themselves “educated” are in fact not literate as they are ill equipped to delve into the intricacies of the language that they read and fully comprehend the implications of what they write.

Literacy can be learned through multiple channels that may or may not include the written word. Some literacy is gained simply through life experience while it can also be gained through vicarious experiences. One of the forms in which literacy can be obtained vicariously is through stories. This is the very first socially institutionalized form of literacy and it predates writing. One of the most prominent examples of tribal method of transmission of literacy that survives in present day culture is the spoken word and particularly, the oral tradition. While the invention of writing and the subsequent spread of literacy among the masses after Gutenberg has altered the oral tradition immensely, it still strives today. The written tradition and the oral tradition both work together to create the linguistic culture that we follow today.

Reading, Writing and its Relationship to Literacy

The ability to read and write is a skill. Literacy, on the other hand, is a characteristic. In a world full of written communication, the skills of reading and writing expose an individual to a wider range of stories and discourses, expanding their horizons and allowing them to refine their emphatic abilities and learn to slip easily into the mind of a person other than themselves. It provides a different perspective that no other format can provide.

Thus, the ability to understand the written word is a useful skill in developing the characteristic of literacy. In fact, there is room for the argument that literacy is not complete without the ability to interact with the written word but at the same time, that ability does not encompass literacy as a whole.

Literacy in the Oral Tradition

Storytelling emerged as a mode of communicating important information in a form that appealed to children. As Mary Poppins would put it, stories became the spoonful of sugar that helped the medicine go down.

My very first experience of literacy was not in relation to the written word. It was with the stories that my father would tell me every night until the age of seven. He would never read them from a book but recite from the memory of his own parents telling him those very same stories as a child. These were the same stories his grandparents told his parents and so on. In this way, he connected me to over 2000 years of history and continued the process of communicating the accumulated knowledge of that family history to posterity. With every retelling, the story changed. It was infused with the beliefs and values of the person who told it and thus, these stories, despite being thousands of years old, remained relevant in the present day. It allowed each individual to passed down to zir children their own subjective view of the world.

In fact, a contemporary definition of mythology is “a subjective truth communicated through stories, symbols and rituals” according to Devdutt Pattanaik (2016). And it is precisely the language that Berry describes, “a language precise and articulate and lively enough to tell the truth about the world as we know it.”(1972) These are simple stories and any literate individual can comprehend the meanings in those stories that lie just below the surface whether they can read those very same stories or not.

This does not mean that someone who has not had experience with the oral tradition is not literate. All it means is that they have not been exposed to the one form of literacy, admittedly the original form of literacy. Just as an individual who cannot read but can understand is literate, an individual who hasn’t been exposed to the oral tradition but can comprehend and articulate well is literate.

The Oral Tradition and Academic Writing

What is fascinating about the transition of stories via oral tradition in families is that these stories do not remain static. Instead, they resemble a game of Chinese Whispers. The story that an individual tells their child might resemble but cannot be an exact replica of what their parents told them. An individual is prone to infuse a story with their own values, beliefs and prejudices at a subconscious level as they retell that story. This is because, at the end of the day, the storytelling process is not purely for entertainment. It is intended to be educational; a means of communicating values and beliefs in a manner that is conducive to reception by a young child. This process also serves to make stories initially thought of a long time ago relevant to the present day.

It is interesting to observe how closely the current process of academic writing resembles this process. Harris describes this process as the adoption of various texts and the integration of those texts into one’s own by creatively infusing the new text with ones own thoughts. According to him, “intellectuals need to say something new and say it well…our creativity has its roots in the work of others – in response, reuse and rewriting.”(2006)

The Current Definition of Literacy and How it Affects Us

By reducing literacy to the ability to read and write, we have reduced the potential that our education system can achieve. We do not necessarily need to compromise quality in order to cope with the quantity. In the world of modernity, we can get away with teaching children how to read but completely ignore the essential skills of critical thinking, analysis and skepticism. This has led to a mediocre level of interaction when it comes to social and political discourse among other issues. It has reduced the quality of life and brought upon a feeling of satisfaction with the given while discouraging the habit of challenging the given in favor of a new idea.

What Next?

The focus of the institutions of education needs to shift from teaching “practical” reading and writing to teaching the slightly “impractical” but ultimately greatly rewarding techniques of comprehension and articulation. (Berry, 1972).

This also needs to extend beyond the classroom. Parents need to encourage critical thinking, skepticism and curiosity. They need to be willing to answer all the questions that a child has from an honest perspective while encouraging the child’s curiosity.

Learning how to read and write is important and must be done. However, it cannot be the society’s benchmark for literacy. Gaining the skills of reading and writing is an important step in becoming literate and once that is achieved, the focus needs to shift to comprehension and articulation.

WORKS CITED

Berry, Wendell. “In Defense of Literacy.” A Continuous Harmony: Essays Cultural & Agricultural. N.p.: Harcourt Brase, 1972.

Pattanaik, Devdutt. “Is Hinduism A Religion, A Myth Or Something Else?” Devdutt. N.p., 7 July 2016. Web. 20 Sept. 2016.

Harris, Joseph. Rewriting: How to Do Things with Texts. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 2006. Print.

Mary Poppins. Dir. Robert Stevenson. By Bill Walsh and Don DaGradi. Perf. Julie Andrews, Dick Van Dyke, David Tomlinson, and Glynis Johns. N.p., n.d. Web.

INTERTEXTUALITY IN FRANKENSTEIN

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein is considered the quintessential Gothic novel but it is far from a simple monster story. Frankenstein is arguably the very first hypertext novel. Reading Frankenstein is like walking through a literary corridor. In this so-called “simple monster story,” Mary Shelley has interwoven multiple doors to texts from her wide reading incorporating increasing levels of complexity into her narrative and just like any other hypertext, her book has been linked as a literary door in other works of art.

One of the most prominent links in Frankenstein is A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, written by Shelley’s mother and namesake, Mary Wollstonecraft. Shelley was obviously greatly influenced by her mother’s views and forwards her ideas about birth, parenting, education and female sexuality in her book. This allows Frankenstein to break away from the common stereotype of a “simple monster story” and adds deep layers of complications to the text. Shelley’s famous work has been alluded to in other works of art as well. Shelley’s “simple monster story” has been invoked by various artists to help them further complicate their own works, most notably Shelley Jackson in her hypertext novel, Patchwork Girl.

One of the most basic elements of a good hypertext novel is the element of choice for the reader. A good hypertext piece allows the reader to interact with the text and make choices about where they want the narrative to go. Frankenstein does something similar. Frankenstein can be read from multiple perspectives. It can be read as a story about parenthood, about morality, about a monster and its creator, about creation itself, about the role of mothers, about the importance of education, about Pandora and her box and many more interpretations. Shelley cleverly leaves her own perspective ambiguous and, by linking to other texts in her piece, threads all those interpretations into her narrative, allowing the reader to take up one or more of those links and go their own way with the text. And just like any good hypertext piece, Frankenstein is used by other artists as a link in their own work as well. One of the many texts that she forwards is her mother’s A Vindication for the Right of Woman and one of the many texts that forwards Frankenstein is Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl.

One of the main themes that Shelley forwards from her mother is that of the relationship between parental duty and filial affection. When Frankenstein succeeds in creating life outside the rules of nature, he panics and leaves his child to fend for itself. This parental neglect becomes the main reason for the transformation of the creature into a monster. Shelley seems to be warning against just the same type of parental neglect for “it is the indispensible duty of men and women to fulfill the duties which give birth to affections that are the surest preservatives against vice.”(Wollstonecraft) By invoking her mother’s famous book, Shelley provides an additional layer of meaning of her novel. She is commenting on the importance of parental responsibility and the adverse effects of parental neglect.

Regardless of his creator’s neglect, the creature manages to get an education in the form of vicarious observation of a family and by reading books. However, the constant loneliness and a desire for connection gives birth to hatred and rage in its heart. This violence leads to the death of a child and the wrongful execution of an innocent girl. The inclusion of this incident in this “simple monster story” was not an accident on Mary Shelley’s part. She was heavily influenced by her mother’s writing and was trying to drive home the point that “a great proportion of misery that wanders, in hideous forms around the world, is allowed to rise from the negligence of parents.”(Wollstonecraft) Interestingly, in Frankenstein, this sentiment is voiced not by the parent but the child, “Do your duty towards me and I will do mine towards you and the rest of mankind.”(Shelley) There is no denying that the creature acts as a monster but there is also no question as to the very human reasons for this monstrosity in the creature. The complexity of the situation begs the question about who the monster is; the parent or the child?

Having failed spectacularly at the duty of a parent, Frankenstein gets an opportunity to redeem himself by fulfilling his duty as the creator of a new species. The creature, taking inspiration from Adam, decides to ask his creator for a female companion. Whether the specificity of the sex of his companion as part of this request was inspired by the creation’s reading of Paradise Lost, his observation of Felix and Safie or was of a sexual nature, the reader can only speculate. Victor initially accepts the deal that his creation proposes but in the middle of the process of creating this companion, he reconsiders and destroys his second creation in an extremely violent manner. This leads to a disastrous series of events that destroy both creator and creation just as Wollstonecraft reminds those who would “either destroy the embryo in the womb, or cast it off when born. Nature, in everything, demands respect and those who violate her laws seldom violate them with impunity.”(Wollstonecraft) In Jackson’s Patchwork Girl, Mary Shelley herself finishes this final creation and “raises” her, developing a strong bond. The life story of this loved and appreciated creation is remarkably different from that of her neglected brother. Jackson, obviously, wishes to highlight neglect on the part of Victor as the root cause of the monstrosity of the creation.

Jackson also comments on the creation’s side of the story. In a hidden lexia that is not linked to any other lexia in the novel and is only accessible through the software’s search engine, the girl thanks her creator.(Clayton) This thematic departure from hatred towards one’s creator to gratitude once again underlines the role that Victor had to play in the hatred that his creation had towards him. However, the structural choice of having this lexia be a hidden one suggests another reading. Just as Jackson could be pointing Victor towards his own faults, it also seems to be reminding the creation that if he had looked for it, he might have found forgiveness in his heart for Victor, allowing both of them to live happier lives.

When Victor is engaged in creating a companion for his creation, a sudden speculation as to the consequences if this female creature who “in all probability was to become a thinking and reasoning animal, might refuse to comply with a compact made before her creation”(Shelley) gives him pause. Mary Wollstonecraft was a woman who refused to abide by the rules made by men before her and reveled in her independence as a free-thinking woman. The influence of this strength of character is evident in Frankenstein. Just like Wollstonecraft’s opponents, Victor was afraid of the consequences of a free, independent woman who can think and reason for herself being let out in the world and the idea was so terrifying to him that he “trembling with passion”(Shelley) destroyed her in an extremely violent manner, one resembling rape, as if controlling the sexuality of this woman would help him control her and “domesticate” her, depriving her of her free will. On the other hand, in Patchwork Girl, the relationship between the creation and the creator develops into a sexual one. Instead of suppressing her creation’s sexuality, the fictitious Mary Shelley embraces it and helps her creation develop it. The difference between the creations in the two works again highlights the impact of how their creators impact their lives.

Mary Shelley invokes her own mother to prove some of the points she is trying to make. Similarly, Shelley is invoked by other artists such as Jackson to enhance their own work. This is why Frankenstein can be considered a hypertext novel in its own right despite the fact that the technology to create hypertext didn’t exist at the time it was written. Having read Frankenstein through the viewpoint of Vindication of the Rights of Woman, it would be very interesting to read it through the other literary doors that Shelley provides as well. Reading other works that link to Frankenstein would also be an amazing experience. It would also be interesting to read Patchwork Girl from the perspective of other books that it links to and see how Frankenstein interacts with them.

WORKS CITED

Jackson, Shelley. Patchwork Girl, Or, A Modern Monster: A Graveyard, a Journal, a Quilt, a Story & Broken Accents. Watertown, MA: Eastgate Systems, 1995. PowerPC.

Shelley, Mary Wollstonecraft, David Lorne Macdonald, and Kathleen Dorothy Scherf. Frankenstein, Or, The Modern Prometheus. Peterborough, Ont.: Broadview, 1999. Print.

Wollstonecraft, Mary. Vindication of the Rights of Woman. Place of Publication Not Identified: Project Gutenberg, 2015. MOBI.

Clayton, Jay. Frankenstein’s futurity:replicants and robots. PDF

Landow, George. “Stitching Together Narrative, Sexuality, Self: Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl | Electronic Book Review.” Stitching Together Narrative, Sexuality, Self: Shelley Jackson’s Patchwork Girl | Electronic Book Review, http://www.electronicbookreview.com/thread/writingpostfeminism/piecemeal

COMING FULL CIRCLE

Hypertext has been perceived as a shiny new form of literature that has the potential to revolutionize the way we tell stories as a culture and has been approached with trepidation lest it disrupt our carefully conceived notions of what literature is. However, the disruption caused by hypertext has not been the disruption caused by the introduction of a new medium but a reversal of the disruption that was caused years ago by the introduction of writing and later, print.

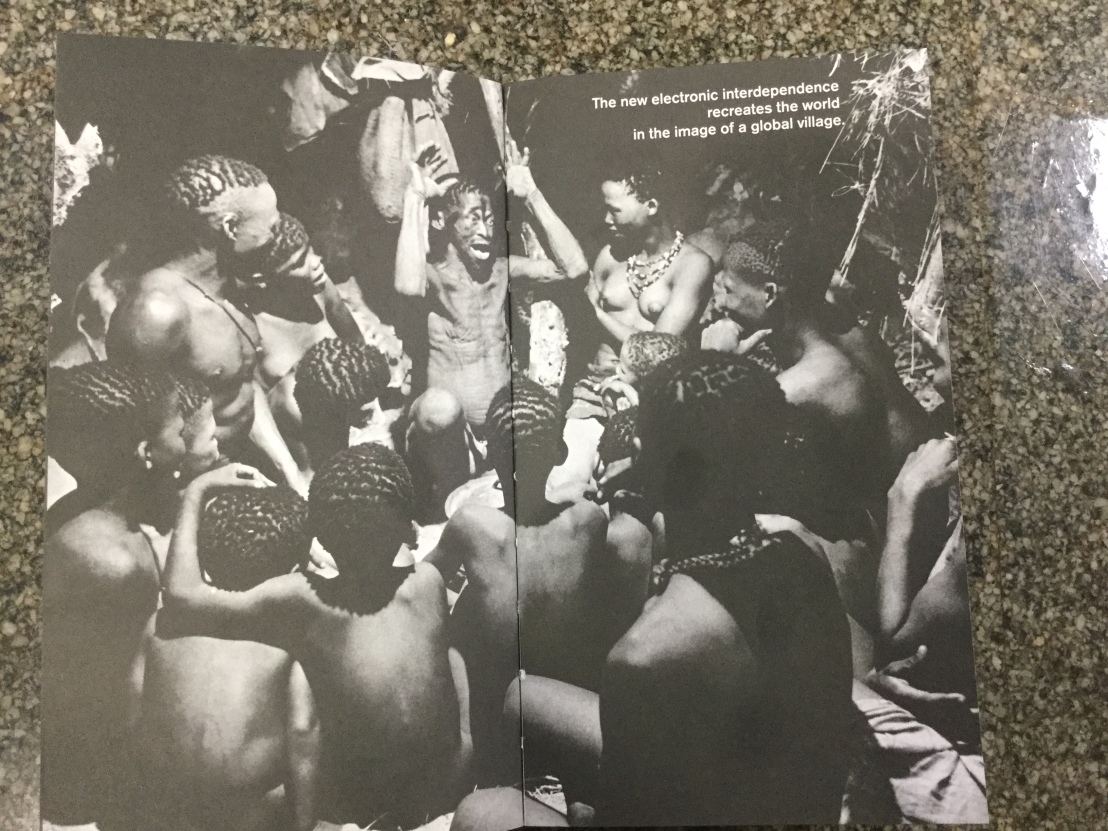

The literary world has its origins in the storytelling traditions of the oral culture. However, these storytelling traditions saw a massive shift with the advent of “the technology of the alphabet” (McLuhan, 45) and later, Gutenberg’s press. Storytelling and story-receiving suddenly became intensely private acts as opposed to social ones and the creative process turned into a solitary undertaking rather than a collaborative one. The introduction of Hypertext brought the communal nature of the oral culture back. Hypertext, once again, enabled collaboration in the creative sphere and a return to “the primordial feeling, the tribal emotions from which a few centuries of literacy divorced us.” (McLuhan, 63) The world of Hypertext, by creating a unique connection between the author and the reader, makes them interdependent on each other for a successful storytelling experience.

(McLuhan, 66-67) Hypertext, being a part of the Internet, connects individuals from across the globe and allows them to collaborate in a way that could never be done before but is reminiscent of the way individuals collaborated in the collectivist cultures of the past.

One of the more recent examples that comes to mind when discussing this is Hearts, Keys and Puppetry by Neil Gaiman and the Twitterverse, a collaborative writing project pioneered by BBC Audio between the writer, Neil Gaiman and his fans. Gaiman posted the very first tweet of the story and then let his fans take the mantle from there with over a thousand contributors following the story and adding to it 140 characters or less at a time. The writing process of Hearts, Keys and Puppetry brought together virtual strangers from all over the world as collaborative writers on a single project with each subsequent writer reading and responding to the story that has been told and then adding their own contribution to take it forward.

This form of writing bears an uncanny similarity to the way The Mahabharata, is being written in the Indian oral tradition for the last 4000 years. The Mahabharata has been written as a community since its inception. Despite having multiple written versions, it is still primarily told in the oral tradition and this allows each teller to tailor the story they heard to fit their own beliefs and purposes when they forward it. As a result, it has multiple off-shoots, subplots and is intensely complicated and immersive. Despite the fact that the official epic of The Mahabharata is over eight times The Iliad and The Odyssey put together, it is still being expanded upon both in the academic as well as the artistic fields.

Another level of similarity between the two is the dynamic of ownership. Being communally written, The Mahabharata is also communally owned. While individuals may own specific parts of it that have been their contributions to this extensive work, The Mahabharata as a whole is owned by the culture and not by an individual. Similarly, while individual tweets, that are a part of the story, are the intellectual property of the tweeter, Hearts, Keys and Puppetry as a whole is communally owned and freely available on Twitter. However, modern capitalism has resulted in the production of an audiobook of this Twitter story, the copyright of which belongs to BBC Audio, thus integrating the communal ownership culture of the pre-literate society with the individual intellectual property culture of the post-literate world.

One of the reasons for the uncanny similarities between The Mahabharata and Hearts, Keys and Puppetry is the choice of Twitter as a medium. Twitter, due to its specific characteristics as a medium could recreate a very similar writing process and communal story-sharing and story-creating environment that the introduction of the alphabet destroyed. As a result, Twitterature (Twitter Literature) has elements of the same kind of communal writing that belongs to the oral culture. Because of its 140-character word limit, Twitter ensured that no single contributor could monopolize the storytelling process and preserved its communal nature. Also, the quick instantaneous nature of the medium along with its wide access expanded the scope of the collaboration to global levels and streamlined the process which, in some ways is an enhancement of the ancient system.

The modernisation of this pre-literate old system has multiple implications beyond ownership. One of the main implications has been in terms of the reader’s interaction with the stories. While print books require readers to be passive vessels receiving knowledge from the author, both oral storytelling and Hypertext require active involvement and interactivity from the reader. For certain readers like Birkerts, this can be a paralyzing experience (151). Birkerts describes his first experience with Hypertext as less than satisfying because he felt “none of the subtle suction exerted by masterly prose.”(151) The decision-making required by hypertext can be overwhelming at times and instill in the reader a fear of missing out. Collaborative writing, due to its range of voices, has a tendency to be intricate and complex which, for some, can be overpowering.

Litzsinger, while tweeting about Hearts, Keys and Puppetry, effectively sums up my opinion of the text as well. The sheer complexity of the text makes the task of editing it seem daunting but it is that very same complexity that makes that very same task seem like an interesting challenge that one would be excited about approaching. The same applies to reading Hearts, Keys and Puppetry and The Mahabharata as well. Their sheer magnitude can be intimidating but that magnitude also makes them immersive and thus, worthwhile.

Another impact that this modernisation has had is on the relationship between readers and writers. Birkerts is of the opinion that the advent of hypertext is “modifying the traditional roles of the writer and reader.”(158) In his view, the communication between the writer and the reader in print media is unidirectional and Hypertext disrupts that by taking power away from the author and allowing the reader to participate in the writing process. For Birkerts, the “author-ity”(159) of the author is essential. While I agree with Birkerts on his observation of these changes, I do not find myself in agreement of his perspective on them. For him, this transition from authoritative to collaborative storytelling has a negative connotation while for me it has positive implications. Birkerts is wary of deconstruction and multiculturalism lest they “disrupt the ideological base upon which aesthetic and cultural hierarchies have been erected.”(159) However, I would argue that aesthetic and cultural hierarchies should not exist in the first place. Egalitarianism and collaboration in the writing process have been the cornerstone of creativity since the very beginning. As Barthes puts it, “a text consists of multiple writings, issuing from several cultures and entering into dialogue with each other, into parody, into contestation; but there is one place where this multiplicity is collected, united, and this place is not the author, as we have hitherto said it was, but the reader”(5-6) Multiculturalism in collaboration with egalitarianism is the most effective way of facilitating the kind of writing that Barthes describes because it is multiculturalism and egalitarianism which create an atmosphere conducive to the kind of dialogue that he refers to. Barthes also highlights the importance of the reader. According to him, it is the reader, not the writer, who should be the central focus of literature and that “the true locus of writing is reading.”(5) This, of course, was true in primitive societies where the oral culture flourished and will be true again due to Hypertext. However, “the birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the Author.” (Barthes, 6) just as Neil Gaiman must step aside, having initiated the process, to let his readers take up the story.

Hypertext has brought back certain elements of the oral culture for us but the modern world is so influenced by the last few centuries of print that the future of literature is unclear. The pressing question of our times is what consequences will the introduction of Hypertext into our print-saturated culture have and to what extent will literacy change due to this.

WORKS CITED

McLuhan, Marshall, Quentin Fiore, and Jerome Agel. The Medium Is the Massage. New York: Bantam, 1967. Print.

Birkerts, Sven. The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. New York: Faber and Faber, 2006. Print.

Litzsinger, Lukas. “@BBCAA I feel Sorry for whoever ends up editing this…and slightly envious. #bbcawdio.” Twitter. N.p., 22 Oct. 2009. Web. 1 Dec. 2016. https://twitter.com/RukasuFox/status/5079524553. Tweet

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Richard Howard. (n.d.): n. pag. Web. 2 Dec. 2016. <http://writing.upenn.edu/~taransky/Barthes.pdf>.