Hypertext has been perceived as a shiny new form of literature that has the potential to revolutionize the way we tell stories as a culture and has been approached with trepidation lest it disrupt our carefully conceived notions of what literature is. However, the disruption caused by hypertext has not been the disruption caused by the introduction of a new medium but a reversal of the disruption that was caused years ago by the introduction of writing and later, print.

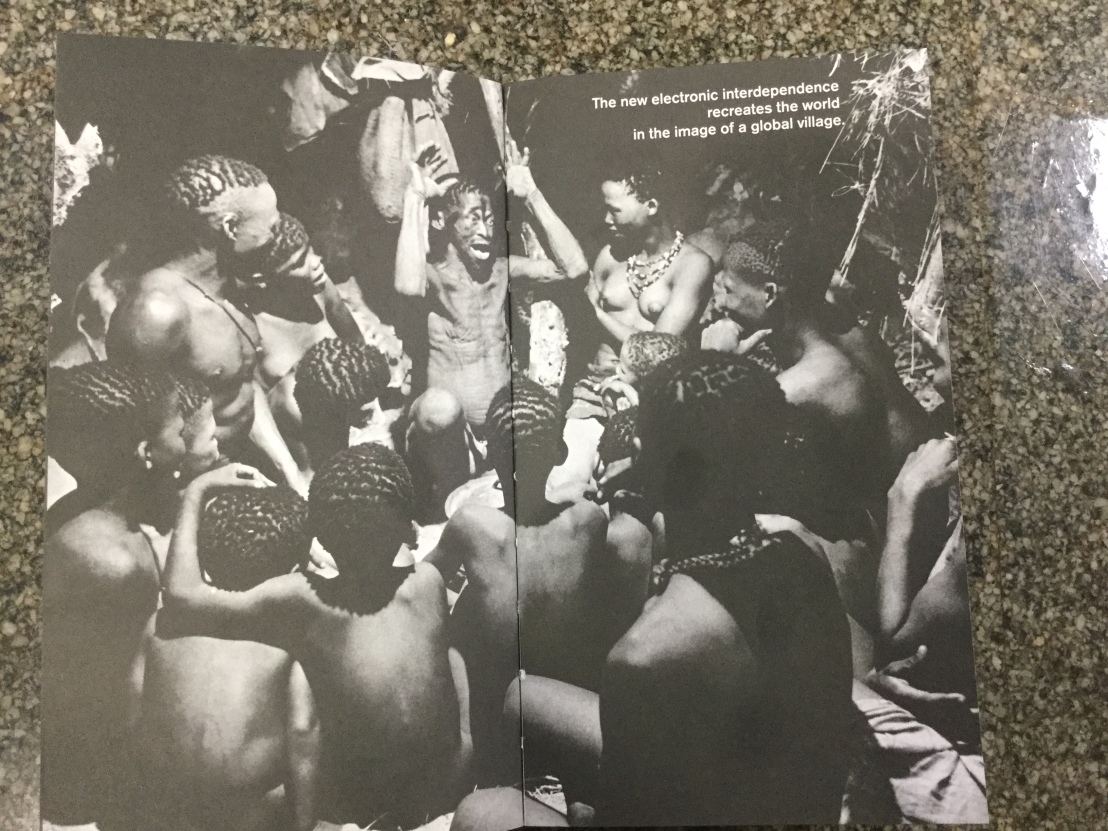

The literary world has its origins in the storytelling traditions of the oral culture. However, these storytelling traditions saw a massive shift with the advent of “the technology of the alphabet” (McLuhan, 45) and later, Gutenberg’s press. Storytelling and story-receiving suddenly became intensely private acts as opposed to social ones and the creative process turned into a solitary undertaking rather than a collaborative one. The introduction of Hypertext brought the communal nature of the oral culture back. Hypertext, once again, enabled collaboration in the creative sphere and a return to “the primordial feeling, the tribal emotions from which a few centuries of literacy divorced us.” (McLuhan, 63) The world of Hypertext, by creating a unique connection between the author and the reader, makes them interdependent on each other for a successful storytelling experience.

(McLuhan, 66-67) Hypertext, being a part of the Internet, connects individuals from across the globe and allows them to collaborate in a way that could never be done before but is reminiscent of the way individuals collaborated in the collectivist cultures of the past.

One of the more recent examples that comes to mind when discussing this is Hearts, Keys and Puppetry by Neil Gaiman and the Twitterverse, a collaborative writing project pioneered by BBC Audio between the writer, Neil Gaiman and his fans. Gaiman posted the very first tweet of the story and then let his fans take the mantle from there with over a thousand contributors following the story and adding to it 140 characters or less at a time. The writing process of Hearts, Keys and Puppetry brought together virtual strangers from all over the world as collaborative writers on a single project with each subsequent writer reading and responding to the story that has been told and then adding their own contribution to take it forward.

This form of writing bears an uncanny similarity to the way The Mahabharata, is being written in the Indian oral tradition for the last 4000 years. The Mahabharata has been written as a community since its inception. Despite having multiple written versions, it is still primarily told in the oral tradition and this allows each teller to tailor the story they heard to fit their own beliefs and purposes when they forward it. As a result, it has multiple off-shoots, subplots and is intensely complicated and immersive. Despite the fact that the official epic of The Mahabharata is over eight times The Iliad and The Odyssey put together, it is still being expanded upon both in the academic as well as the artistic fields.

Another level of similarity between the two is the dynamic of ownership. Being communally written, The Mahabharata is also communally owned. While individuals may own specific parts of it that have been their contributions to this extensive work, The Mahabharata as a whole is owned by the culture and not by an individual. Similarly, while individual tweets, that are a part of the story, are the intellectual property of the tweeter, Hearts, Keys and Puppetry as a whole is communally owned and freely available on Twitter. However, modern capitalism has resulted in the production of an audiobook of this Twitter story, the copyright of which belongs to BBC Audio, thus integrating the communal ownership culture of the pre-literate society with the individual intellectual property culture of the post-literate world.

One of the reasons for the uncanny similarities between The Mahabharata and Hearts, Keys and Puppetry is the choice of Twitter as a medium. Twitter, due to its specific characteristics as a medium could recreate a very similar writing process and communal story-sharing and story-creating environment that the introduction of the alphabet destroyed. As a result, Twitterature (Twitter Literature) has elements of the same kind of communal writing that belongs to the oral culture. Because of its 140-character word limit, Twitter ensured that no single contributor could monopolize the storytelling process and preserved its communal nature. Also, the quick instantaneous nature of the medium along with its wide access expanded the scope of the collaboration to global levels and streamlined the process which, in some ways is an enhancement of the ancient system.

The modernisation of this pre-literate old system has multiple implications beyond ownership. One of the main implications has been in terms of the reader’s interaction with the stories. While print books require readers to be passive vessels receiving knowledge from the author, both oral storytelling and Hypertext require active involvement and interactivity from the reader. For certain readers like Birkerts, this can be a paralyzing experience (151). Birkerts describes his first experience with Hypertext as less than satisfying because he felt “none of the subtle suction exerted by masterly prose.”(151) The decision-making required by hypertext can be overwhelming at times and instill in the reader a fear of missing out. Collaborative writing, due to its range of voices, has a tendency to be intricate and complex which, for some, can be overpowering.

Litzsinger, while tweeting about Hearts, Keys and Puppetry, effectively sums up my opinion of the text as well. The sheer complexity of the text makes the task of editing it seem daunting but it is that very same complexity that makes that very same task seem like an interesting challenge that one would be excited about approaching. The same applies to reading Hearts, Keys and Puppetry and The Mahabharata as well. Their sheer magnitude can be intimidating but that magnitude also makes them immersive and thus, worthwhile.

Another impact that this modernisation has had is on the relationship between readers and writers. Birkerts is of the opinion that the advent of hypertext is “modifying the traditional roles of the writer and reader.”(158) In his view, the communication between the writer and the reader in print media is unidirectional and Hypertext disrupts that by taking power away from the author and allowing the reader to participate in the writing process. For Birkerts, the “author-ity”(159) of the author is essential. While I agree with Birkerts on his observation of these changes, I do not find myself in agreement of his perspective on them. For him, this transition from authoritative to collaborative storytelling has a negative connotation while for me it has positive implications. Birkerts is wary of deconstruction and multiculturalism lest they “disrupt the ideological base upon which aesthetic and cultural hierarchies have been erected.”(159) However, I would argue that aesthetic and cultural hierarchies should not exist in the first place. Egalitarianism and collaboration in the writing process have been the cornerstone of creativity since the very beginning. As Barthes puts it, “a text consists of multiple writings, issuing from several cultures and entering into dialogue with each other, into parody, into contestation; but there is one place where this multiplicity is collected, united, and this place is not the author, as we have hitherto said it was, but the reader”(5-6) Multiculturalism in collaboration with egalitarianism is the most effective way of facilitating the kind of writing that Barthes describes because it is multiculturalism and egalitarianism which create an atmosphere conducive to the kind of dialogue that he refers to. Barthes also highlights the importance of the reader. According to him, it is the reader, not the writer, who should be the central focus of literature and that “the true locus of writing is reading.”(5) This, of course, was true in primitive societies where the oral culture flourished and will be true again due to Hypertext. However, “the birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the Author.” (Barthes, 6) just as Neil Gaiman must step aside, having initiated the process, to let his readers take up the story.

Hypertext has brought back certain elements of the oral culture for us but the modern world is so influenced by the last few centuries of print that the future of literature is unclear. The pressing question of our times is what consequences will the introduction of Hypertext into our print-saturated culture have and to what extent will literacy change due to this.

WORKS CITED

McLuhan, Marshall, Quentin Fiore, and Jerome Agel. The Medium Is the Massage. New York: Bantam, 1967. Print.

Birkerts, Sven. The Gutenberg Elegies: The Fate of Reading in an Electronic Age. New York: Faber and Faber, 2006. Print.

Litzsinger, Lukas. “@BBCAA I feel Sorry for whoever ends up editing this…and slightly envious. #bbcawdio.” Twitter. N.p., 22 Oct. 2009. Web. 1 Dec. 2016. https://twitter.com/RukasuFox/status/5079524553. Tweet

Barthes, Roland. “The Death of the Author.” Trans. Richard Howard. (n.d.): n. pag. Web. 2 Dec. 2016. <http://writing.upenn.edu/~taransky/Barthes.pdf>.